| James D. Watson | |

James D. Watson | |

| Born | April 6, 1928 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Residence | U.S., UK |

| Nationality | United States |

| Fields | Molecular biology |

| Institutions | Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory |

| Alma mater | University of Chicago, Indiana University |

| Doctoral advisor | Salvador Luria |

| Known for | DNA structure, Molecular biology |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize (1962) |

| Religious stance | None (Atheist)[1][2] |

James Dewey Watson (born April 6, 1928) is an American molecular biologist, best known as one of the co-discoverers of the structure of DNA. Watson, Francis Crick, and Maurice Wilkins were awarded the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for their discoveries concerning the molecular structure of nucleic acids and its significance for information transfer in living material".[3] He studied at the University of Chicago and Indiana University and subsequently worked at the University of Cambridge's Cavendish Laboratory in England where he first met his future collaborator and personal friend Francis Crick.

In 1956 he became a junior member of Harvard University's Biological Laboratories until 1976, but in 1968 served as Director of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on Long Island, New York and shifted its research emphasis to the study of cancer. In 1994 he became its President for ten years, and then subsequently served as its Chancellor until 2007, when he was forced into retirement by controversy over several comments about race and intelligence. Between 1988 and 1992 he was associated with the National Institutes of Health, helping to establish the Human Genome Project. He has written many science books, including the seminal textbook The Molecular Biology of the Gene (1965) and his bestselling book The Double Helix (1968) about the DNA Structure discovery.

Biography

Watson was born in Chicago, Illinois, on April 6, 1928, to the son of a businessman, also named James Dewey Watson, and Margaret Jean Mitchell.[4] His father was of Scottish descent (both Dewey and Watson being Scottish surnames).[5] His mother's father Lauchlin Mitchell, a tailor, was from Glasgow, Scotland, and her mother, Lizzie Gleason, was the child of Irish parents from Tipperary.[6] Watson was fascinated with bird watching, a hobby he shared with his father.[7] Watson appeared on Quiz Kids, a popular radio show that challenged precocious youngsters to answer questions.[8] Thanks to the liberal policy of University president Robert Hutchins, he enrolled at the University of Chicago at the age of 15.[9] After reading Erwin Schrödinger's book What Is Life? in 1946, Watson changed his professional ambitions from the study of ornithology to genetics.[10] He earned his B.S. in Zoology from the University of Chicago in 1947. In his autobiography, Avoid Boring People, Watson describes the University of Chicago as an idyllic academic institution where he was instilled with the capacity for critical thought and an ethical compulsion not to suffer fools who impeded his search for truth, in contrast to his description of his later work at Harvard University.[11]

He was attracted to the work of Salvador Luria. Luria eventually shared a Nobel Prize for his work on the Luria-Delbrück experiment, which concerned the nature of genetic mutations. Luria was part of a distributed group of researchers who were making use of the viruses that infect bacteria, called bacteriophages. Luria and Max Delbrück were among the leaders of this new "Phage Group", an important movement of geneticists from experimental systems such as Drosophila towards microbial genetics. Early in 1948 Watson began his Ph.D. research in Luria's laboratory at Indiana University and that spring he got to meet Delbrück in Luria's apartment and again that summer during Watson's first trip to the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL).[12] The Phage Group was the intellectual medium within which Watson became a working scientist. Importantly, the members of the Phage Group had a sense that they were on the path to discovering the physical nature of the gene. In 1949 Watson took a course with Felix Haurowitz that included the conventional view of that time: that proteins were genes and able to replicate themselves.[13] The other major molecular component of chromosomes, DNA, was thought by many to be a "stupid tetranucleotide", serving only a structural role to support the proteins. However, even at this early time, Watson, under the influence of the Phage Group, was aware of the Avery-MacLeod-McCarty experiment, which suggested that DNA was the genetic molecule. Watson's research project involved using X-rays to inactivate bacterial viruses.[14] He gained his Ph.D. in Zoology at Indiana University in 1950 (at age 22).

Watson then went to Copenhagen in September 1950 for a year of postdoctoral research, first heading to the laboratory of biochemist Herman Kalckar.[7] Kalckar was interested in the enzymatic synthesis of nucleic acids, and wanted to use phages as an experimental system. Watson, however, wanted to explore the structure of DNA, and his interests did not coincide with Kalckar's.[15] After working part of the year with Kalcker, Watson spent the remainder of his time in Copenhagen conducting experiments with microbial physiologist Ole Maaloe, then a member of the Phage Group.[16] The experiments, which Watson had learned of during the previous summer's Cold Spring Harbor phage conference, included the use of radioactive phosphate as a tracer to determine which molecular components of phage particles actually infect the target bacteria during viral infection.[15] The intention was to determine whether protein or DNA was the genetic material, but upon consultation with Max Delbrück,[15] they determined that their results were inconclusive and could not specifically identify the newly labeled molecules as DNA.[17] Watson never developed a constructive interaction with Kalckar, but he did accompany Kalckar to a meeting in Italy where Watson saw Maurice Wilkins talk about his X-ray diffraction data for DNA.[7] Watson was now certain that DNA had a definite molecular structure that could be solved.[18]

In 1951 the chemist Linus Pauling published his model of the protein alpha helix, a result that grew out of Pauling's relentless efforts in X-ray crystallography and molecular model building. After obtaining some results from his phage and other experimental research conducted at Indiana University, Statens seruminstitute (Denmark), Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, and the California Institute of Technology, Watson now had the desire to learn to perform X-ray diffraction experiments so that he could work to determine the structure of DNA. That summer, Luria met John Kendrew and arranged for a new postdoctoral research project for Watson in England.[7]

Watson and Crick proceeded to deduce the double helix structure of DNA which they submitted to the journal Nature and was subsequently published on April 25, 1953.

The discovery was made on February 28, 1953; the first Watson/Crick paper appeared in Nature on April 25,1953. Sir Lawrence Bragg, the director of the Cavendish Laboratory, where Watson and Crick worked, gave a talk at Guys Hospital Medical School in London on Thursday, May 14, 1953 which resulted in an article by Ritchie Calder in The News Chronicle of London, on Friday, May 15, 1953, entitled "Why You Are You. Nearer Secret of Life." The news reached readers of The New York Times the next day; Victor K. McElheny, in researching his biography, "Watson and DNA: Making a Scientific Revolution", found a clipping of a six-paragraph New York Times article written from London and dated May 16, 1953 with the headline "Form of `Life Unit' in Cell Is Scanned." The article ran in an early edition and was then pulled to make space for news deemed more important.(The New York Times subsequently ran a longer article on June 12, 1953). The Cambridge University undergraduate newspaper Varsity also ran its own short article on the discovery on Saturday, May 30th, 1953. Bragg's original announcement of the discovery at a Solvay conference on proteins in Belgium on 8 April 1953 went unreported by the press!

Watson subsequently presented a paper on the double helical structure of DNA at the 18th Cold Spring Harbor Symposium on Viruses in early June 1953, six weeks after the publication of the Watson/Crick paper in Nature; many at the meeting had not yet heard of the discovery. The 1953 Cold Harbor Symposium was the first opportunity to see the model of the DNA Double Helix.

[19] Watson, Crick, and Wilkins were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962 for their research on the structure of nucleic acids.[3] Some regret that Rosalind Franklin did not live long enough to share in the Nobel Prize.[20] Watson mentions in his autobiography, Avoid Boring People, that he was refused a $1,000 raise in salary after winning the Nobel Prize.[11]

In 1968, Watson married Elizabeth Lewis and became the Director of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Between 1970 and 1972 Watson's two sons were born and by 1974 the young family made CSH their permanent residence. Watson served as the Laboratory's Director and President for 35 years, and later assumed the role of Chancellor. In October 2007 Watson resigned as a result of controversial remarks about race made to the press. Watson has one son who has schizophrenia.[21]

The Double Helix

In 1968 Watson wrote The Double Helix, one of the Modern Library's 100 best non-fiction books. The account is the sometimes painful story of not only the discovery of the structure of DNA, but the personalities, conflicts and controversy surrounding their work.

Controversy attended the publication of the book. Harvard professor Richard Lewontin wrote that the book had "debased the currency of his [Watson's] own life", and molecular biologist Robert L. Sinsheimer described Watson's portrayal of science as a "clawing climb up a slippery slope, impeded by the authority of fools, to be made with cadged data ... with malice toward most, and charity toward none." [11] It was originally to be published by Harvard University Press, but after objections from both Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins, among others, Watson's home university where he had been a member of the biology faculty since 1955, dropped the book and it was instead published by a commercial publisher, an incident which caused some scandal. Watson's original title was to have been "Honest Jim," in part to raise the ethical questions of bypassing Rosalind Franklin to gain access to her X-ray diffraction data before they were published. If all that mattered was beating Pauling to the structure of DNA, then Franklin's cautious approach to analysis of the X-ray data was simply an obstacle that Watson needed to run around. Wilkins and others were there at the right time to help Watson and Crick do so.

The Double Helix changed the way the public viewed scientists and the way they work.[22] In the same way, Watson's first textbook, The Molecular Biology of the Gene, set a new standard for textbooks, particularly through the use of concept heads—brief declarative subheadings. Its style has been emulated by almost all succeeding textbooks. His next great success was Molecular Biology of the Cell, although here his role was more that of coordinator of an outstanding group of scientist-writers. His third textbook was Recombinant DNA, which used the ways in which genetic engineering has brought much new information about how organisms function. The textbooks are still in print.

Genome project

In 1989, Watson's achievement and the success led to his appointment as the Head of the Human Genome Project at the National Institutes of Health, a position he held until April 10, 1992.[23] Watson left the Genome Project after conflicts with the new NIH Director, Bernadine Healy. Watson was opposed to Healy's attempts to acquire patents on gene sequences, and any ownership of the "laws of nature." Two years before stepping down from the Genome Project, he had stated his opinion on this long and ongoing controversy which he saw as an illogical barrier to research; he said, "The nations of the world must see that the human genome belongs to the world's people, as opposed to its nations." He left within weeks of the 1992 announcement that the NIH would be applying for patents on brain-specific cDNAs.[24] In 1994, Watson became President of CSHL. Francis Collins took over the role as Director of the Human Genome Project. Watson became the second person[25] to publish his fully sequenced genome online[26], after it was presented to him on May 31, 2007 by 454 Life Sciences Corporation[27] in collaboration with scientists at the Human Genome Sequencing Center, Baylor College of Medicine. "'I am putting my genome sequence on line to encourage the development of an era of personalized medicine, in which information contained in our genomes can be used to identify and prevent disease and to create individualized medical therapies,' said CSHL Chancellor Watson."[28]

Awards and decorations

|

|

On Saturday, October 20 1962 the award of Nobel prizes to John Kendrew and Max Perutz, and to Crick, Watson, and Wilkins was satirised in a short sketch in the BBC TV programme That Was The Week That Was with the Nobel Prizes being referred to as 'The Alfred Nobel Peace Pools'; in this sketch Watson was called "Little J.D. Watson" and "Who'd have thought he'd ever get the Nobel Prize? Makes you think, doesn't it".

Career

At Harvard University, starting in 1956, Watson achieved a series of academic promotions from Assistant Professor, to Associate Professor to full Professor of Biology. He championed a switch in focus for the school from classical biology to molecular biology, stating that disciplines such as ecology, developmental biology, taxonomy, physiology, etc. had stagnated and could only progress once the underlying disciplines of molecular biology and biochemistry had elucidated their underpinnings, going so far as to discourage their study by students. He left the school in 1976.[11]

Watson joined the staff of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in 1968. In a retrospective summary of his accomplishments there, Bruce Stillman, the laboratory's president said, "Jim Watson created a research environment that is unparalleled in the world of science." It was "under his direction [that the Lab has] made major contributions to understanding the genetic basis of cancer." Generally in his roles as Director, President, and Chancellor, Watson led CSHL to its present day mission, which is "dedicat[ion] to exploring molecular biology and genetics in order to advance the understanding and ability to diagnose and treat cancers, neurological diseases, and other causes of human suffering." In October, 2007, Watson was suspended following criticism of views on race and intelligence attributed to him, and a week later, on the 25th, he retired at the age of 79 from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory from what the lab called "nearly 40 years of distinguished service",[36] In a statement, Watson attributed his retirement to his age, and circumstances that he could never have anticipated or desired.[37]

In January 2007, Watson accepted the invitation of Leonor Beleza, president of the Champalimaud Foundation, to become the head of the foundation's scientific council, an advisory organ. He will be in charge of selecting the remaining council members.[38]

As of 2008, Watson is the Institute advisor for the newly-formed Allen Institute for Brain Science [39]. The Institute, located in Seattle, Washington, was founded in 2003 by Philanthropists Paul G. Allen and Jody Allen Patton as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit corporation and medical research organization. A multidisciplinary group of neuroscientists, molecular biologists, informaticists, engineers, mathematicians, statisticians, and computational biologists have been brought together to form the scientific core of the Allen Institute. Utilizing the mouse model system, these fields have joined together to investigate expression of 20,000 genes in the adult mouse brain and to map gene expression to a cellular level beyond neuroanatomic boundaries. The data generated from this joint effort is contained in the publicly available Allen Brain Atlas application located at www.brain-map.org. Upon completion of the Allen Brain Atlas, this consortium of scientists will pursue additional questions to further our understanding of neuronal circuitry and the neuroanatomic framework that defines the functionality of the brain.

Watson is the only living pioneer in early DNA research; dead pioneering scientists include Rosalind Franklin, Maurice Wilkins, and James Watson's former colleague Francis Crick.

Honorary degrees received

|

|

Professional & honorary affiliations

|

|

Political activism

During his tenure as a professor at Harvard, Watson participated in several political protests:

- Vietnam War: While a professor at Harvard University, Watson, along with "12 Faculty members of the department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology" including one other Nobel prize winner, spearheaded a resolution for "the immediate withdrawal of U.S. forces' from Vietnam."[40]

- Nuclear proliferation and environmentalism: In 1975, on the "thirtieth anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima," Watson along with "over 2000 scientists and engineers" spoke out against nuclear proliferation to President Ford in part because of the "lack of a proven method for the ultimate disposal of radioactive waste" and because "The writers of the declaration see the proliferation of nuclear plants as a major threat to American liberties and international safety because they say safeguard procedures are inadequate to prevent terrorist theft of commercial reactor-produced plutonium."[41]

Controversies

Watson's sometimes abrasive and aggressive personality (once described by E. O. Wilson as "the most unpleasant human being I had ever met"[11]) has made him the subject of several controversies; the controversy over his book The Double Helix was merely one such example. In his autobiography, Avoid Boring People, he describes his academic colleagues as "dinosaurs", "deadbeats", "fossils", "has-beens", "mediocre", and "vapid".[11]

Use of King's College results

An enduring controversy has been generated by Watson and Crick's use of DNA X-ray diffraction data collected by Rosalind Franklin and Raymond Gosling. The controversy arose from the fact that some of Franklin's unpublished data was used by Watson and Crick in their construction of the double helix model of DNA.[42] Franklin's experimental results provided estimates of the water content of DNA crystals and these results were consistent with the two sugar-phosphate backbones being on the outside of the molecule. Franklin personally told Crick and Watson that the backbones had to be on the outside. Her identification of the space group for DNA crystals revealed to Crick that the two DNA strands were antiparallel. The X-ray diffraction images collected by Gosling and Franklin provided the best evidence for the helical nature of DNA. Franklin's experimental work thus proved crucial in Watson and Crick's discovery. Watson and Crick had three sources for Franklin's unpublished data: 1) her 1951 seminar, attended by Watson, 2) discussions with Wilkins, who worked in the same laboratory with Franklin, 3) a research progress report that was intended to promote coordination of Medical Research Council-supported laboratories. Watson, Crick, Wilkins and Franklin all worked in MRC laboratories.

Prior to publication of the double helix structure, Watson and Crick had little interaction with Franklin. Crick and Watson felt that they had benefited from collaborating with Wilkins. They offered him a co-authorship on the article that first described the double helix structure of DNA. Wilkins turned down the offer, a fact that may have led to the terse character of the acknowledgment of experimental work done at King's College in the eventual published paper. Rather than make any of the DNA researchers at King's College co-authors on the Watson and Crick double helix article, the solution that was arrived at was to publish two additional papers from King's College along with the helix paper. Biographer Brenda Maddox suggested that because of the importance of her work to Watson and Crick's model building, Franklin should have had her name on the original Watson and Crick manuscript.[43] Franklin may have never known the extent to which her unpublished data had helped in the double helix discovery. According to one critic, unprotected by libel laws, Watson's portrayal of Franklin in The Double Helix was negative, giving the appearance that she was Wilkins' assistant and was unable to interpret her own DNA data.[44]

In his book The Double Helix, Watson described being intimidated by Franklin and that they were unable to establish constructive scientific interactions during the time period when Franklin was doing DNA research. In the book's epilogue, written after Franklin's death, Watson acknowledges his early impressions of Franklin were often wrong, that she faced enormous barriers as a woman in the field of science even though her work was superb, and that it took years to overcome their bickering before appreciating Franklin's generosity and integrity.

A review of the handwritten correspondence from Franklin to Watson, located in the archives at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, reveals that the two scientists later had exchanges of constructive scientific correspondence. In fact, Franklin consulted with Watson on her Tobacco Mosaic Virus RNA research. Franklin's letters begin on friendly terms with "Dear Jim", and conclude with equally benevolent and respectful sentiments like "Best Wishes, Yours, Rosalind". Each of the scientists published their own unique contributions to the discovery of the structure of DNA in separate articles, and all of the contributors published their findings in the same volume of Nature. These classic molecular biology papers are identified as: Watson J.D. and Crick F.H.C. "A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid" Nature 171, 737-738 (1953),[19] Wilkins M.H.F., Stokes A.R. & Wilson, H.R. "Molecular Structure of Deoxypentose Nucleic Acids" Nature 171, 738-740 (1953),[45] Franklin R. and Gosling R.G. "Molecular Configuration in Sodium Thymonucleate" Nature 171, 740-741 (1953).[46] Franklin did not receive a Nobel Prize for her important contribution because the Nobel Prize is not awarded posthumously.[47]

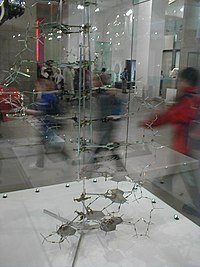

The wording on the DNA sculpture (which was donated by Watson) outside Clare College's Memorial Court, Cambridge, England is:

On the base:

- "These strands unravel during cell reproduction. Genes are encoded in the sequence of bases."

- "The double helix model was supported by the work of Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins."

On the helices:

- "The structure of DNA was discovered in 1953 by Francis Crick and James Watson while Watson lived here at Clare."

- "The molecule of DNA has two helical strands that are linked by base pairs Adenine - Thymine or Guanine - Cytosine."

The aluminium sculpture stands fifteen feet high. It took a pair of technicians two weeks to build it. For the artist responsible it was an opportunity to create a monument that brings together the themes of science and nature; Charles Jencks, Sculptor said "It embraces the trees, you can sit on it and the ground grows up and it twists out of the ground. So it's truly interacting with living things like the turf, and that idea was behind it and I think it does celebrate life and DNA". Tony Badger, Master of Clare, said: "It is wonderful to have this lasting reminder of his achievements while [James Watson] was at Clare and the enormous contribution he and Francis Crick have made to our understanding of life on earth."

Statement claiming links between race and intelligence

On October 14, 2007, a biographical article written by one of Watson's former assistants[48], Charlotte Hunt-Grubbe, appeared in the Sunday Times Magazine in anticipation of his soon to be released, in the UK, memoir Avoid Boring People: Lessons from a Life in Science.[48]

Watson was quoted as saying he was "inherently gloomy about the prospect of Africa" as

| “ | all our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours — whereas all the testing [IQ and Standardized testing] says not really.[48] | ” |

Hunt-Grubbe stated that Watson's "hope" was "everyone is equal" but quoted him as having said "people who have to deal with black employees find this not true." Furthermore, she suggested that Watson believed "you should not discriminate on the basis of colour" by quoting him as having said

| “ | there are many people of colour who are very talented, but don’t promote them when they haven’t succeeded at the lower level.[48] | ” |

Watson was then attributed as having written

| “ | there is no firm reason to anticipate that the intellectual capacities of peoples geographically separated in their evolution should prove to have evolved identically. Our wanting to reserve equal powers of reason as some universal heritage of humanity will not be enough to make it so.[48] | ” |

The quotes attributed to him drew attention and criticism from press in several countries and were widely discussed on CNN[49], the BBC[50], several papers[51], peers and by civil rights advocates.[52] The common perception was that of Watson claiming a link between race and intelligence with the BBC stating that "[Watson] claimed black people were less intelligent than white people".[50] In his book, the origin of the final written quote, Watson does not directly mention race as a factor in his hypothesized divergence of intellect between geographically isolated populations.[53]

On October 18, The Science Museum in London cancelled a talk that Watson was scheduled to give the following day,[50] stating that they believed Watson's comments had "gone beyond the point of acceptable debate." On the same day the Board of Trustees at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory suspended Watson's administrative responsibilities, stating that

| “ | this action follows the Board’s public statement yesterday disagreeing with the comments attributed to Dr. Watson in the October 14, 2007 edition of The Sunday Times U.K.[54] that they "vehemently disagree with...and are bewildered and saddened" by.[51] | ” |

Francis Collins, director of the National Human Genome Research Institute, a position inherited from Watson, said

| “ | I am deeply saddened by the events of the last week...in the aftermath of a racist statement...that was both profoundly offensive and utterly unsupported by scientific evidence.[51] | ” |

On October 19, Watson issued an apology, stating that he was "mortified" and "cannot understand how I could have said what I am quoted as having said."[55][56] He also claimed to

| “ | understand why people, reading those words, have reacted in the ways they have ... To all those who have drawn the inference from my words that Africa, as a continent, is somehow genetically inferior, I can only apologize unreservedly. That is not what I meant. More importantly from my point of view, there is no scientific basis for such a belief.[57] | ” |

Clarifying his position further, Watson explained

| “ | I have always fiercely defended the position that we should base our view of the world on the state of our knowledge, on fact, and not on what we would like it to be. This is why genetics is so important. For it will lead us to answers to many of the big and difficult questions that have troubled people for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. ...Since 1978, when a pail of water was dumped over my Harvard friend E O Wilson for saying that genes influence human behaviour, the assault against human behavioural genetics by wishful thinking has remained vigorous. But irrationality must soon recede ... science is not here to make us feel good. It is to answer questions in the service of knowledge and greater understanding. ...We do not yet adequately understand the way in which the different environments in the world have selected over time the genes which determine our capacity to do different things. The overwhelming desire of society today is to assume that equal powers of reason are a universal heritage of humanity. It may well be. But simply wanting this to be the case is not enough. This is not science. To question this is not to give in to racism. This is not a discussion about superiority or inferiority, it is about seeking to understand differences, about why some of us are great musicians and others great engineers.[56][57] | ” |

Despite Watson's expressed belief in the importance of scientific inquiry into the relationship between heredity and intelligence, a number of news sources reported that Watson was "retracting" his earlier statements on this topic. For example, the journal Nature reported

| “ | Watson has apologized and retracted the outburst... He acknowledged that there is no evidence for what he claimed about racial differences in intelligence.[58] | ” |

Nature went on to say that the controversy and cancellations potentially could suppress scientific inquiry by geneticists who are studying the differences between different human population groups.[58] Medical Hypotheses (not peer-reviewed) went further, saying that "The unjustified ill treatment meted out to Watson therefore requires setting the record straight about the current state of the evidence on intelligence, race, and genetics.", and summarised evidence that apparently supports his position, declaring "These are facts, not opinions and science must be governed by data. There is no place for the “moralistic fallacy” that reality must conform to our social, political, or ethical desires."[59]

Despite the apology and subsequent attempt to clarify his position the controversy continued. He returned to the US and Cold Spring Harbor on the 19th October putting his further engagements in doubt. The University of Edinburgh formally retracted an invitation to the "DNA, Dolly and Other Dangerous Ideas: The Destiny of 21st Century Science" Enlightenment Lecture on October 22.[60]

Watson resigned from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on October 25.[49][61] Watson cited reasons for his retirement other than the controversy, though did refer to it.

| “ | Closer now to 80 than 79, the passing on of my remaining vestiges of leadership is more than overdue. The circumstances in which this transfer is occurring, however, are not those which I could ever have anticipated or desired.[62] | ” |

On December 9, 2007, a Sunday Times article[63] reported a claim by deCODE Genetics that 16% of Watson's DNA is of African origin and 9% is of Asian origin. deCODE's methods were not reported and details of the analysis were not published. According to deCODE's Kari Stefansson, the analysis relied on an error-ridden version of Watson's full genome sequence, and Stefansson "doubts [. . .] whether the 16 percent figure will hold up"[64] In 2008 Watson was interviewed by Henry Louis Gates regarding his views on race, intelligence, and other controversial subjects.[65]

In 2006 during an interview with Charlie Rose and E. O. Wilson, Watson stated that some people want to believe that evolution stopped 100,000 years ago. He stated that he did not agree with this view and that human differences are not trivial.[66]

Other statements

- Watson has repeatedly supported genetic screening and genetic engineering in public lectures and interviews, arguing that stupidity is a disease and the "really stupid" bottom 10% of people should be cured.[67] He has also suggested that beauty could be genetically engineered, saying "People say it would be terrible if we made all girls pretty. I think it would be great."[67]

- He has been quoted in The Sunday Telegraph as stating: "If you could find the gene which determines sexuality and a woman decides she doesn't want a homosexual child, well, let her."[68] The biologist Richard Dawkins wrote a letter to The Independent claiming that Watson's position was misrepresented by The Sunday Telegraph article, and that Watson would equally consider the possibility of having a heterosexual child to be just as valid as any other reason for abortion, to emphasise that Watson is in favor of allowing choice.[69]

- On the issue of obesity, Watson has also been quoted as saying: "Whenever you interview fat people, you feel bad, because you know you're not going to hire them."[70]

- Watson also had quite a few disagreements with Craig Venter regarding his use of EST fragments while Venter worked at NIH. Venter went on to found Celera genomics and continued his feud with Watson through the privately funded venture. Watson was even quoted as calling Venter "Hitler."[71]

- While speaking at a conference in 2000, Watson had suggested a link between skin color and sex drive, hypothesizing that dark-skinned people have stronger libidos.[70][72] His lecture, complete with slides of bikini-clad women, argued that extracts of melanin — which give skin its color — had been found to boost subjects' sex drive. "That's why you have Latin lovers," he said, according to people who attended the lecture. "You've never heard of an English lover. Only an English patient." [73]

0 comments:

Post a Comment